Historic Native American Santo Domingo Poly chrome Bowl, Ca 1910, #1129 SOLD

$ 2,187.50

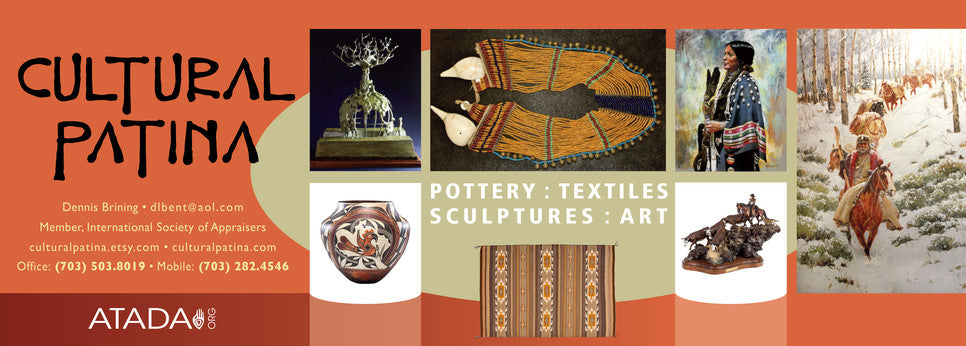

Historic Native American

Santo Domingo Poly chrome Bowl, Ca 1910, #1129

Description: #1129 Historic Native American Santo Domingo Poly chrome Bowl, Ca 1910,

Dimensions: 9.5" x 3.5"

Condition: In overall excellent condition. No breaks, cracks, or chips. Surface with minor wear. No apparent restoration.

Some background

Kewa Pueblo (Eastern Keres [kʰewɑ], Navajo: Tó Hájiiloh), formerly known as Santo Domingo Pueblo, is an Indian pueblo and a census-designated place (CDP) in Sandoval County, New Mexico, in the United States. The pueblo is located approximately 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Santa Fe. Interstate 25 runs 4 miles (6 km) to the east of the community. As of the 2000 census, the CDP population was 2,550 and is nearly 99% Native American. The CDP is part of the Albuquerque Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The population of the pueblo is composed of Native Americans who speak Keres, an eastern dialect of the Keresan languages. Like several other pueblo peoples, they have a matrilineal kinship system, in which children are considered born into the mother's family and clan, and inheritance and property pass through the maternal line.

The Pueblo celebrates an annual feast day on August 4 to honor their patron saint, Saint Dominic. More than 2,000 pueblo people participate in the traditional corn dances held at this time.

In the 17th century, the Spanish conquistadors named the pueblo as Santo Domingo. Its earliest recorded name was Gipuy. According to Pueblo Council members, the local name in their Keres language has always been Kewa. In 2009, the pueblo officially changed its name to Kewa Pueblo, altering its seal, signs and letterhead.[1]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 2.0 square miles (5.2 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 2,550 people, 446 households, and 408 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 1,273.9 people per square mile (492.3/km²). There were 475 housing units at an average density of 237.3 per square mile (91.7/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 98.71% Native American, 0.24% White, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.78% from other races, and 0.24% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.18% of the population.

There were 446 households out of which 38.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.3% were married couples living together, 38.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 8.3% were non-families. 7.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 1.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 5.72 and the average family size was 6.02.

In the CDP, the population was spread out with 37.0% under the age of 18, 11.6% from 18 to 24, 28.7% from 25 to 44, 16.4% from 45 to 64, and 6.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females there were 106.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.6 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $26,563, and the median income for a family was $28,382. Males had a median income of $20,878 versus $17,768 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $6,038. About 36.5% of families and 36.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 43.7% of those under age 18 and 27.5% of those age 65 or over.

History

The pueblo plays a supporting role in Spanish colonial history. Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, a fugitive from the Crown, was arrested at the pueblo in March 1591. Castaño, a notorious slaver, had fled capture. He pursued an illegal claims expedition up the Pecos River, which had not yet been seen by Europeans. He made it as far as Pecos pueblo, and raided it for slaves. He turned west and traveled toward modern-day Santa Fe, which had been established by the Spanish. He followed the Rio Grande river valley south. On orders of the Viceroy at Mexico City, Captain Juan Morlette found Castaño at Kewa pueblo and arrested him. He returned him to authorities to face trial for his crimes, including his attack on Pecos pueblo.[citation needed]

Castaño abandoned two interpreters at Kewa Pueblo; he had kidnapped them earlier and brought them with him. Governor Juan de Oñate's expedition recorded encountering Tomas and Cristobal at Kewa Pueblo, as it traveled north.[citation needed]

20th century to present

Potters of Kewa (Santo Domingo) and Cochiti pueblos have made traditional pots for centuries, developing styles for different purposes and expressing deep beliefs in their designs. Since the early decades of the 20th century, these pots have been appreciated by a wider audience outside the pueblos. Continuing to use traditional techniques, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, potters have also expanded their designs and repertoire in pottery, which has an international market.

Notes

1. Constable, Anne (9 March 2010), "Pueblo returns to traditional name: Santo Domingo quietly becomes 'Kewa'; tribe alters seal, signs and letterhead", The New Mexican (Santa Fe, New Mexico), archived here at WebCite

2. "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

3. "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

Further reading

Chapman, Kenneth Milton (1977). The Pottery of Santo Domingo Pueblo: A Detailed Study of Its Decoration. School of American Research, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, ISBN 0-8263-0460-5; original published in 1936 as volume 1 of the Memoirs of the Laboratory of Anthropology OCLC 3377512

Verzuh, Valerie K. (2008). A River Apart: The Pottery of Cochiti and Santo Domingo Pueblos. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ISBN 978-0-89013-522-8 (Source: Wikipedia)

A History of Pueblo Pottery:

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive.

Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un-decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Santo Domingo Poly chrome Bowl, Ca 1910, #1129

Description: #1129 Historic Native American Santo Domingo Poly chrome Bowl, Ca 1910,

Dimensions: 9.5" x 3.5"

Condition: In overall excellent condition. No breaks, cracks, or chips. Surface with minor wear. No apparent restoration.

Some background

Kewa Pueblo (Eastern Keres [kʰewɑ], Navajo: Tó Hájiiloh), formerly known as Santo Domingo Pueblo, is an Indian pueblo and a census-designated place (CDP) in Sandoval County, New Mexico, in the United States. The pueblo is located approximately 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Santa Fe. Interstate 25 runs 4 miles (6 km) to the east of the community. As of the 2000 census, the CDP population was 2,550 and is nearly 99% Native American. The CDP is part of the Albuquerque Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The population of the pueblo is composed of Native Americans who speak Keres, an eastern dialect of the Keresan languages. Like several other pueblo peoples, they have a matrilineal kinship system, in which children are considered born into the mother's family and clan, and inheritance and property pass through the maternal line.

The Pueblo celebrates an annual feast day on August 4 to honor their patron saint, Saint Dominic. More than 2,000 pueblo people participate in the traditional corn dances held at this time.

In the 17th century, the Spanish conquistadors named the pueblo as Santo Domingo. Its earliest recorded name was Gipuy. According to Pueblo Council members, the local name in their Keres language has always been Kewa. In 2009, the pueblo officially changed its name to Kewa Pueblo, altering its seal, signs and letterhead.[1]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 2.0 square miles (5.2 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 2,550 people, 446 households, and 408 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 1,273.9 people per square mile (492.3/km²). There were 475 housing units at an average density of 237.3 per square mile (91.7/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 98.71% Native American, 0.24% White, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.78% from other races, and 0.24% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.18% of the population.

There were 446 households out of which 38.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.3% were married couples living together, 38.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 8.3% were non-families. 7.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 1.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 5.72 and the average family size was 6.02.

In the CDP, the population was spread out with 37.0% under the age of 18, 11.6% from 18 to 24, 28.7% from 25 to 44, 16.4% from 45 to 64, and 6.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females there were 106.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.6 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $26,563, and the median income for a family was $28,382. Males had a median income of $20,878 versus $17,768 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $6,038. About 36.5% of families and 36.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 43.7% of those under age 18 and 27.5% of those age 65 or over.

History

The pueblo plays a supporting role in Spanish colonial history. Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, a fugitive from the Crown, was arrested at the pueblo in March 1591. Castaño, a notorious slaver, had fled capture. He pursued an illegal claims expedition up the Pecos River, which had not yet been seen by Europeans. He made it as far as Pecos pueblo, and raided it for slaves. He turned west and traveled toward modern-day Santa Fe, which had been established by the Spanish. He followed the Rio Grande river valley south. On orders of the Viceroy at Mexico City, Captain Juan Morlette found Castaño at Kewa pueblo and arrested him. He returned him to authorities to face trial for his crimes, including his attack on Pecos pueblo.[citation needed]

Castaño abandoned two interpreters at Kewa Pueblo; he had kidnapped them earlier and brought them with him. Governor Juan de Oñate's expedition recorded encountering Tomas and Cristobal at Kewa Pueblo, as it traveled north.[citation needed]

20th century to present

Potters of Kewa (Santo Domingo) and Cochiti pueblos have made traditional pots for centuries, developing styles for different purposes and expressing deep beliefs in their designs. Since the early decades of the 20th century, these pots have been appreciated by a wider audience outside the pueblos. Continuing to use traditional techniques, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, potters have also expanded their designs and repertoire in pottery, which has an international market.

Notes

1. Constable, Anne (9 March 2010), "Pueblo returns to traditional name: Santo Domingo quietly becomes 'Kewa'; tribe alters seal, signs and letterhead", The New Mexican (Santa Fe, New Mexico), archived here at WebCite

2. "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

3. "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

Further reading

Chapman, Kenneth Milton (1977). The Pottery of Santo Domingo Pueblo: A Detailed Study of Its Decoration. School of American Research, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, ISBN 0-8263-0460-5; original published in 1936 as volume 1 of the Memoirs of the Laboratory of Anthropology OCLC 3377512

Verzuh, Valerie K. (2008). A River Apart: The Pottery of Cochiti and Santo Domingo Pueblos. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ISBN 978-0-89013-522-8 (Source: Wikipedia)

A History of Pueblo Pottery:

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive.

Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un-decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Related Products

Sold out

Sold out